Communications, Steamship Lines, and the American Civil War

This post was originally published on the Journal of the Civil War Era’s blog, Muster, on January 23, 2018, at https://www.journalofthecivilwarera.org/2018/01/communications-steamship-lines-american-civil-war/.”

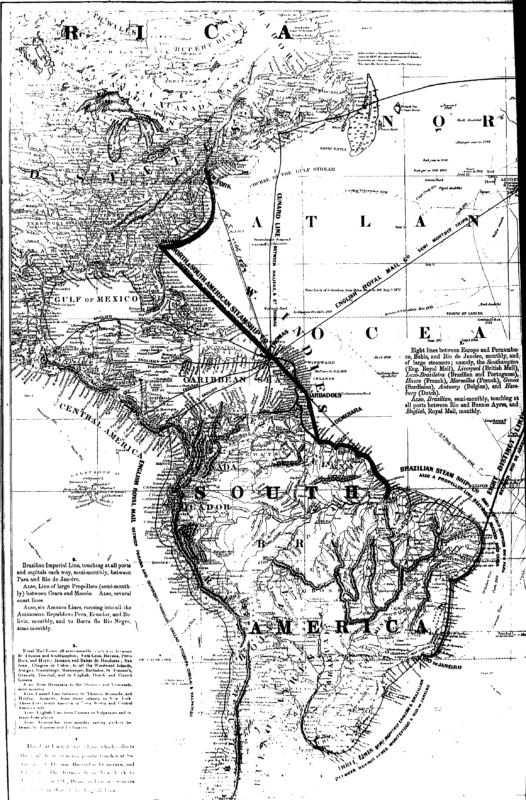

Today, a simple click and mere seconds separate the writer and reader of a message; they communicate instantaneously with one another across vast distances. In the middle of the nineteenth century, weeks could pass before a letter reached its recipient on the other side of the ocean. Civil War armies benefited from the use of telegraphs, which were still slow by modern standards, but oceans presented significant barriers.1 By the time of the Civil War, steam power had conquered time and space on iron rails and made an impact on the high seas. Boosters and merchants in port cities along the eastern seaboard increasingly desired to enhance trade and communication by attracting regular, direct trade lines. Some Civil War era officials foresaw the potential of steamships as agents of empire. Direct communications with other countries in the Americas could offer an opportunity to outmaneuver European rivals and establish an informal U.S. empire. The Civil War witnessed a continuation of the promotion of trade links and foreshadowed the imperial connections of the decades following the war.

In 1860, cargo and people still travelled on slow sailing vessels, but the role of steamships was growing in importance. For example, in 1860, merchants and ship owners in the British Empire operated 2,337 steamships; in addition, there were 36,164 sailing vessels.2 Lucrative mail routes and mail packet routes attracted steamers. Representatives negotiated postal agreements that not only included low postage rates but also stipulated transportation on board steamships, usually in direct communications between New York and the signatory country. For example, when the Hanseatic City of Bremen dispatched Rudolph M. Schleiden to the United States in 1853, his first task was to negotiate a postal agreement, setting postage rates at a lower price and thus hopefully drawing all German post through Bremen. The eventual result was in 1860 the emergence of Bremen’s Norddeutscher Lloyd (Lloyd), following in the footsteps of the Hamburg-Amerikanische Packetfahrt-Actien-Gesellschaft (HAPAG). Both used steamers for the transportation of mail and passengers between the North German port cities and New York.3 Just like on other transatlantic routes, U.S.-owned business were not competitive.4

However, without reliable and safe service, customers might not patronize these new steamlines. Schleiden emphasized that the German steamship companies needed to provide reliable service and rent replacement ships if their own vessels suffered engine trouble, or worse.5 During the Congressional debates surrounding passage of these agreements, Southern representatives voiced their desire for Southern states to also receive direct service to Europe.6 Their requests assumed new urgency with secession.

Secession severed not only the political ties between North and South, but also their trade links. The vast majority of vessels and trade arrived in Northern ports, but many ships left Southern ports with valuable cargos. To foster trade links between Europe and the seceded states, consuls in Southern ports communicated home the urgent desire for direct links. Before even the formation of the Confederates States of America, Hamburg’s merchant-consul Johannes Nicolaus Hudtwalcker in Savannah asked the Staatsyndicus (equivalent to the U.S. Secretary of State) Carl Hermann Merck to consider the growing trade between the two cities and promote a line between Hamburg and Savannah. The consul pointed out that the lack of a direct connection between the two forced all commerce to travel through other ports. Hudtwalcker suggested the creation of a direct line, claiming such traffic would yield significant profits. He pointed to the excellent connections with the hinterland in Hamburg to illustrate the city’s ability to transship transport commodities from Savannah to other German states.7 Hudtwalcker was not alone in this request for a direct connection between a port in the seceded states and Europe. Such an inquiry shortly after secession signals that many merchants-consuls, like other contemporaries, did not consider war likely, instead seeing peaceful separation as a distinct possibility. However, regardless of secession’s outcome, they needed to plan how maintain their trade relations.

The dialog about connecting southern ports with the world did not stop with the outbreak of war. Conversations about enhancing trade and communications were not restricted to European countries. In October 1863, the U.S. Minister to Brazil, James W. Webb, informed the State Department about Brazil’s intention to open a subsidized steamship line to New York, which would also stop in Charleston. Well aware of Secretary of State William Seward’s hemispheric vision, Webb presented the proposal in a hemispheric perspective, aiming to establish an “American Policy.” As the most powerful country on the continent, the United States could not tolerate communications with South America to happen by way of Europe, since in time of war, Europe could prevent any interaction between North and South America. Ironically, Webb’s Europhobic attitude clouded his judgment. He suggested that the constitutional governments of the Americas needed to work together against Europe’s oppressive monarchies, overlooking the fact that Brazil was a European-style monarchy. Nevertheless, even the leader of Argentina voiced the perception of “neglect of the Government of South America by the Government of Washington, in not furnishing a direct Steam Mail communication with Brazil.” Harshly criticizing British policy and shipping as piratical, due to the supposed support the British had granted to the Confederacy, Webb noted that U.S. neglect had allowed Great Britain to turn the region into an economic dependent. Besides the trade benefits of a steamship line, Webb pointed out that mail steamers were self-sufficient. Webb concluded that “looking at this question solely in a National and Political point of view, and in connexion with our future relations with the Government of this Continent, I am of opinion, that it would be wise, and sound statesmanship, to pay a million of Dollars per annum for two Mails per month to and from Brazil, even if they would insure no immediate increase of commerce, and even if I did not believe, as I most assuredly do, that the proposed Steamers will not only be self-remunerating, but would within the term of the proposed contract, directly and indirectly benefit our Country more than a hundred fold.”8 Interestingly, Webb did not explain why he wanted the Lincoln administration to support a shipping line that apparently connected New York to Charleston before heading into the Caribbean and South America.

Where Webb saw the steamship as a tool against Great Britain and an agent of empire for the United States, the ships would have also docked in Confederate ports, fostering what Hudtwalcker had suggested to Hamburg in early 1861. Steamships could increase trade and speed-up communications, but at the same time, they could also project power. When the Civil War started, merchants and ship owners continued to seek economic growth opportunities. Hudtwalcker and Webb’s arguments confirm Jay Sexton’s recent argument that steam transportation and imperial expansion went hand in hand. Viewing the Civil War era’s international communication discussions as part of long-term trends illustrates that regardless of the war, trade continued to grow and politicians in the United States considered the imperial future of their country.

Niels Eichhorn is an assistant professor of history at Middle Georgia State University. He holds a Ph.D. in History from the University of Arkansas. His first book, Separatism and the Language of Slavery: A Study of 1830 and 1848 Political Refugees and the American Civil War, is under contract with LSU Press. He has published articles on Civil War diplomacy in Civil War History and American Nineteenth Century History.

Sources

- The transatlantic cable was laid in 1858 but was operational for only one month. It was not until 1866 that they were successful in establishing transatlantic telegraph capabilities.

- United Kingdom, Annual Statement of the Trade and Navigation of the United Kingdom (London, UK: George Edward Eyre and William Spottiswoode, 1861), 50.

- Ludwig Beutin, Bremen und Amerika: Zur Geschichte der Weltwirtschaft und der Beziehungen Deutschlands zu den Vereinigten Staaten (Bremen, Germany: Schünemann, 1953), 117.

- Jay Sexton, “Steam Transport, Sovereignty, and Empire in North America, 1850-1885,” Journal of the Civil War Era 7, no. 4 (December 2017): 629.

- Schleiden to Senats-Commission für die auswärtigen Angelegenheiten, July 29, 1858, 2-B.13.b.1.a.2.b.II, Staatsarchiv Bremen.

- Schleiden to Senats-Commission für die auswärtigen Angelegenheiten, March 6, 1857, 2-B.13.b.1.a.2.b.I, Staatsarchiv Bremen.

- Johannes Nicolaus Hudtwalcker to Carl Hermann Merck, January 31, 1861, CL VI, no 16p, Vol 4b, Fasc 13c, 111-1 Senat, Staatsarchiv der Freien und Hansestadt Hamburg.

- James Watson Webb to William Henry Seward, October 8, 1863, M121, Despatches From U.S. Ministers To Brazil, 1809-1906, National Archives, Washington, DC. For the financial benefits of a subsidized steam ship line, see Sexton’s discussion of the Pacific Mail/Panama Railroad. Sexton, “Steam Transport, Sovereignty, and Empire in North America,” 631-635.

www.hudtwalcker.com 2019