The Captain in the Mists of Time

According to the archives, one Captain Hutwalker was, for many years, employed in the service of the King of Denmark during the Thirty Years War (1618 – 1648).

In 1638, Imperial forces threatened to attack Holstein, then under the Danish crown. The Danish king, King Christian IV, ordered some of his troops ”Uthschuss uth Jüthlandt, Holstein und Dithmarschen”, to take up quarter in the area. Following the King’s order, two regiments consisting mostly of foot soldiers, were quickly stationed in the southern part of Dithmarschen. Here they remained from Michaelmas in 1638 until Easter in 1640. The regiments are named after their commanding officers, Begker (Becker) and Hoetwalker. In the week after Easter in 1640, both regiments were again on the move, this time to Glückstadt, where a considerable tax is to be paid to the Imperial troops as compensation for plunder. All then remains peaceful until late 1643, but in December 1643 the Swedish Field marshal Torstenson1 invaded Holstein. This marks the beginning of the second half of the war, the so-called Schwedische Krieg (Swedish War), lasting from 1643 to 1645.

Regarding the hero of this short tale of events long ago, the officer Hoetwalker, it is told that he, in the middle of December 1643, together with 150 battle ready men and a couple of canons, are on the move to the fortress of Krempe, northeast of Glückstadt, to act as reinforcements. On the 19th February 1644 Captain Hoetwalker is given command of 200 men, and sent out into the Wiltermarsh with the order to occupy it. Unfortunately, the archives give no reports of what eventually unfolds in the swampy district of the Wiltermarsh, or any accounts of the expected bravery of the aforementioned Captain. In the wake of the ensuing peace of Brømsebro2 on 13th August 1645, the participation of Denmark-Norway, and the Duchies, in the Thirty Year’s War,3 is finally over.

The on-going and seemingly endless war had caused enormous losses for all parties involved, but especially so for Schleswig-Holstein. When peace is restored there are many issues to be dealt with. However, for the crown, the most pressing concern after the war is to raise enough money to pay the soldiers in order they can be dismissed from active duty.

Among the officers to leave active duty is our Captain Hudtwalker. His former companion in arms, Becker, has on the 29th January 1644, been appointed to Major. To such a handsome and fine man the most important question now is what shall a retired Captain, recently dismissed from an army he has honourably served for years, do to earn his living?

One can only imagine how the question troubles him. After the war, and fighting, the area and country can perhaps be called not just a geographical marsh, but also an economic one. Fortunately, the hero of this tale of times past shows himself to be a man of common sense and practical skills. Displaying his usual vigor, the captain soon decides on a course of action. To his advantage, the war has not been entirely unprofitable. During his years in the King’s service, he has cautiously and methodically managed to put aside some money. He can thus embark on a new career with a good weight of coins tucked in his purse.

Where there has been devastation in the past, there ought to be possibilities for the future, or so one may think the good Captain reasons. The marshes are not just swamps. On the contrary, the area has indeed fertile soil. Observing this, the Capitain does the only sensible thing; he settles down. Although a fertile soil underneath one’s feet in itself is a blessing when starting anew, it is not enough for a young man to build a future life on. And soon enough it becomes clear that the Captain also has other things on his mind. The heart is a lonely hunter, and after the strenous and long, bleak days as a soldier, he yearns to be able to share his bed and table with a suitable companion. There seems to be several promising candidates around, many of them well suited too, for his new life as a family man.

Much to the regret of the chronicler, the archives remain remarkably silent on this topic. But for as a keen an investigator as the chronicler of this tale, nothing is left to chance or escapes attention. With so few sources at hand, and such a thrilling story to tell, even the smallest details may conceal matters of the utmost importance. The magnifying glass is properly polished and the old and fragmented archives closely examined. Finally, after much labour, a short entry in the ”Rechnungsbuch des viertel Brunsbüttel” from 1646 catches the chronicler’s watchful eye. The entry, albeit very short indeed, simply states that a Herr Capitain Huedtwalker paid 4 marks for a property. As most of the devoted readers of these columns will have observed by now, the last name (regardless of the spelling) is not common. To the contrary it is quite rare, and even remains so to this day. One can therefore quite rightfully presume it refers to the one and same Captain, who is the hero of our tale.

It might also be added at this point that the chronicler does not believe in coincidences. Everything happens for some reason. Things appear as a coincidence, and at first sight meaningless or chaotic, but that is simply because we fail to understand, and grasp, the purpose. What thus may appear as a coincidence, is, to the chronicler, a hidden purpose. The hand of fate, a more dramatically inclined person, would perhaps say. However, the chronicler is well aware that his view is not shared by everybody.

Anyhow, returning to our main theme, the tale of the brave Capitain, peace is something precious and therefore, like any precious item, always vunerable. Nothing, except our souls, lives forever, and the peace everybody had yearned for unfortunately does not last. As always there is a snake lurking in the grass, even in the tranquil and fertile grounds of these sparsely populated marshlands. Again it is a Swedish snake, most deadly and evil, full of greed and wicked schemes. And, some years later, the cruel Swedes are back on the warpath. During the ensuing war with Sweden (Polackenkriege in Schleswig-Holstein) in 1658-1660, the pictoresque and quiet town of Brunsbüttel, is severly plundered.

The archives must have suffered from this Swedish plague too, because from this stage on, the chronicler observes that the archives sadly reveal very little informtion about our captain and his fate. What we do know, however, is that Captain Johann Huedtwalker in 1661-74 is mentioned as the owner of a small piece of land of 8 Morgen and 6 Scheffeln. Then we know of four children born to Baltazar Hans von Buchwald and Katharina Margareta Hutwalker.

(1645/46 – 1699/1700)

Another source give her name as Cathrine Margrethe Hudtwalcher, born in Brunsbüttel on 1 January 1645/46, as a daughter to Johan Hudtwalker. But from that point onwards, the trail of the Capitain himself grows cold. Silence reigns and our tale should abruptly have ended. Given the wars, including the 1st and 2nd WW, the plunders and the passing of time, it is altogether amazing that so much of the original archives have survived

However, as any clever investigator fully knows, determination and patience are among his most important tools. Fortunately the chronicler of this tale possess both these qualities. Although the path of our hero has by now become invisible, by a flickering torchlight the chronicler again carefully studies, and ponders each and every possible and impossible source. Meticulously the chronicler examin the ground covered by dust of rumors. And there, in the uttermost remote corner of observance, almost to thin and frail to be noticed with the bare eye, shimmers the golden weaving of an Ariadne’s thread. Holding the torchlight above his head, the chronicler bends down. The thin and fragile tread winds its way down the ancient and narrow steps leading to the forgotten basement of the archives. Engulfed in his study, the chronicler pays no heed to the darkness surrounding him, but carefully follow the thread to a beautifully ornamented box placed on a scarlet piece of cloth. Barely able to conceal his exitement, the chronicler takes a deep breathe and slowly open the decorated lid. Inside is a document, yellow with age and thorn at the edges, containing a complete and detailed record of the Capitain’s family.

”Oh, my dear Capitain,” the chronicler whisper triumphantly, ”it seems you indeed found a most promising candidate to become your darling wife!”

Johann Hudtwalcker (1608 – d. 28.10.1678)

Parents

Unknown

Siblings

Claus Hudtwalcker (d. 1714)

Dierk Hudtwalcker (d. 1725)

Johann Hudtwalcker (b. 1638 – d. 1705)

Catharina Margrethe Hudtwalcker (b. 1 January 1645/46, Brunsbüttel – d. 1 January 1699/1700, Süderhastedt)

Jacob Hudtwalcker (d. 10 November 1680, Marne)

Hein Hudtwalcker (d. 25 October 1693)

Anna Hudtwalcker

Harm Hudtwalcker

Hinrich Hudtwalcker

Margaretha Hudtwalcker

Spouse

Margaretha (last name unknown, d. 1691)

Chronicler’s comments

History is to a large extent a mystery.

It is not an exact science.

A wise man once said that history, as thought in schools and universities, is nothing but a fable convenu.

Too easily one projects one’s own perceptions and notions into the object, instead of letting the object itself speak and reveal its true nature. And as history unfolds, it’s own history, the history of history, is created.

The chronicler as the historian is fumbling around in the dark. In the pale and flickering light he might see something (or believe he sees something), but what it is remains a mystery. Only a combination of facts and an open mindset of free thoughts not hindered by prejudice, might help reveal the true nature of the objects he perceives.

The chronicler as the historian is fumbling around in the dark. In the pale and flickering light he might see something (or think he sees something) but what it is remains a mystery and only a combination of facts and a lively imagination might help reveal what he perceives to be its true nature.

Even with the best possible sources at hand, one may only catch a vague glimpse into what really happened.

The tale of the brave and illustrious Capitain Hoetwalker/Hutwalker/Hudtwalker/Huedtwalker is no exception. Unfortunately, the records are incomplete and the archives inadequate. The ultimate truth remains shrouded by the mists of time. Thus, the complete story of the Captain will most probably never be known.

However, the chronicler would like to invite the reader to take part in an effort to solve at least some aspects, or riddles, of this mystery. We do so by using the method of deduction so kindly described by Sherlock Holmes in A Study in Scarlet:

“It is a capital mistake to theorize before you have all the evidence. It biases the judgement.”

With the method now firmly at hand, and with a rather limited amount of evidence, the chronicler would like to point out the following:

The various and different spellings of the last name in this text are all according to the archives. Considering the educational standards of the time, in our case especially when it comes to spelling, grammar and local dialects, it is fair to assume that the spelling of last names in different ways, was nothing unusual at the time. As one has already observed from this tale, it was also the case with other last names, most specifically in connection with the Capitain’s companion from the campaign in 1640: the officer Begker/Becker.

The last name of our hero is indeed so rare (up to this day, too) that the chronicler (who, as the reader may remember, does not believe in coincidences) cannot but argue that the different variations refer to the one and same man.

In the beginning of the tale of our Captain, we hear he is stationed in Dithmarschen.

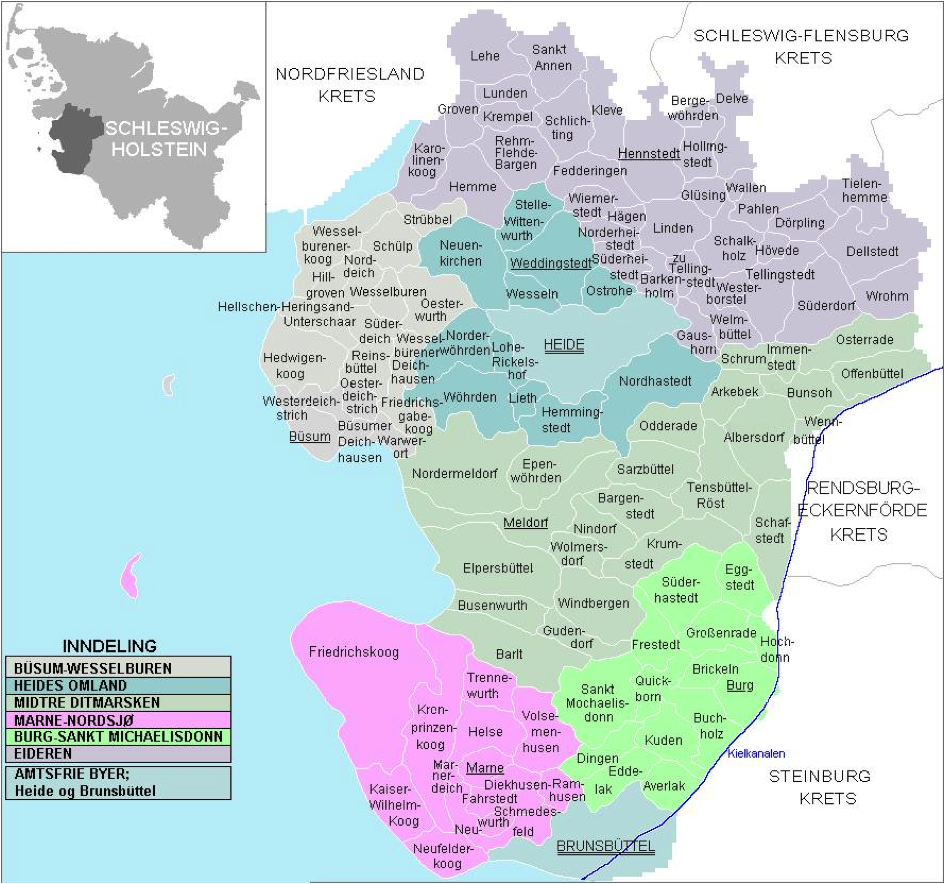

Dithmarschen is a district located on the North Sea, embraced by the river Elbe to the south, and the river Eider to the south. As the devoted reader of these pages undoubtedly will have observed, the cradle of everything Hudtwalcker is the village of Lüdingworth, in the county of Hadeln, near Cuxhaven. The “Land Hadeln” is farming country on the southern tip of the river Elbe, not far from where it joins the North Sea close to Cuxhaven.

It is a geographical fact that this is very close to where Captain Huedtwalker settled down around 1646.

Another point of interest to the innovative and keen chronicler of this text, are the years of from when the Captain Huedtwalker leaves the army (1644) and the years of the first records of the Hudtwalcker family. Referring to the article Through The Ages on this website, the chronicler wishes to mention that the first Hudtwalcker recorded is Johann Hudtwalcker (1608 – 1678).

Referring once more to the same article, the last point to be scrutinized underneath the magnifying glass is the striking coincidence of surnames:

Johann married Margaretha (dead 1691, year of birth and surname not known). The couple had ten children. (Source: Through The Ages)

We know that Captain Johann Huedtwalker in 1661-74 is mentioned in official records in

Holstein. We know of four children born to Baltazar Hans von Buchwald and Katarina Margareta Hutwalker. We know too, that naming children after their mothers and fathers were not an uncommon practice in those days.

The chronicler has now gone through the evidence and presented all known facts.

It is up to the devoted reader to draw his, or hers, own conclusions, and, if one dare, to form a judgement.

Sources and inspiration

The chronicler is grateful to the meticulous work by Mr. Flemming Kobbersøe Skov, Denmark

He would also like to express his most sincere thanks to Mr. Rodrigo Hudtwalcker Z. of Lima, Peru, who made him aware of the Captain, and to Simon Kennerley, Commander of The Yorkshire Irregulars, for his invaluable contribution.

Notes

- In 1643, Sweden’s armies, under the command of Lennart Torstenson, then suddenly invaded Denmark without declaring war, this war became known as the Torstenson War. The Netherlands, wishing to end the Danish stranglehold on the Baltic, joined the Swedes in their war against Denmark–Norway. In October 1644 a combined Dutch-Swedish fleetdestroyed 80 percent of the Danish fleet in the Battle of Femern. The result of this defeat proved disastrous for Denmark–Norway: in the Second treaty of Brömsebro (1645) Denmark ceded to Sweden the Norwegian provinces Jemtland, Herjedalen and Älvdalen as well as the Danish islands of Gotland and Øsel. Halland went to Sweden for a period of 30 years and the Netherlands were exempt from paying the Sound Duty.

- The Second Treaty of Brömsebro (or the Peace of Brömsebro) was signed on 13 August 1645, and ended the Torstenson War, a local conflict that began in 1643 and was part of the larger Thirty Years’ War) between Sweden and Denmark-Norway. Negotiations for the treaty began in February the same year.

- The Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648) was a series of wars principally fought in Central Europe, involving most of the countries of Europe. It was one of the most destructive conflicts in European history, and one of the longest continuous wars in modern history.

Initially, religion was a motivation for war as Protestant and Catholic states battled it out even though they all were inside the Holy Roman Empire. Changing the relative balance of power within the Empire was at issue. Gradually, it developed into a more general conflict involving most of the great powers of Europe. In this general phase, the war became less specifically religious and more a continuation of the Bourbon–Habsburg rivalry for European political pre-eminence, leading in turn to further warfare between France and the Habsburg powers.

A major consequence of the Thirty Years’ War was the devastation of entire regions, denuded by the foraging armies (bellum se ipsum alet). Famine and disease significantly decreased the population of the German states, Bohemia, the Low Countries, and Italy; most of the combatant powers were bankrupted. While the regiments within each army were not strictly mercenary, in that they were not units for hire that changed sides from battle to battle, some individual soldiers that made up the regiments were mercenaries. The problem of discipline was made more difficult by the ad hoc nature of 17th-century military financing; armies were expected to be largely self-funding by means of loot taken or tribute extorted from the settlements where they operated. This encouraged a form of lawlessness that imposed severe hardship on inhabitants of the occupied territory.

The Thirty Years’ War was ended with the treaties of Osnabrück and Münster, part of the wider Peace of Westphalia.Some of the quarrels that provoked the war went unresolved for a much longer time.

www.hudtwalcker.com 2014