It’s All About Soul

An imaginary tale of recollections

In December 1967, the same year The Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,and I was about to nosedive into the tormenting quagmire called puberty, my uncle and cousin travelled from sunny Spain to spend Christmas with us pale northerners in the land of eternal ice and snow.

Distances were longer back then. Travelling to Oslo no easy task. Perhaps incomprehensible to the Nordic mind, but the truth was that not many, if at all any, travelled from Spain to partake in the beauty of the Norwegian winter wonderland in the late 1960s. It’s a fair guess to say that the majority of the Spanish population did not know that we in the Nordic region had been using skis for 5000 years. On the other hand, Spain was still unknown territory to most Norwegians. There were few charter flights. No parties on the beaches were pigs were grilled, no drunken Norwegians puking over the restaurant tables. In the virgin days of mass tourism, Spain had an exotic flavour of eternal sunshine, oranges, flamenco and bullfights. To some, however, it was not all about sunshine and cheap wine. Spain also had a dark stain of civil war and dictatorship. Although he had settled in Barcelona for health reasons, and to be closer to artists he had befriended, and decades after Hemingway wrote about death in the afternoon, my uncle got slightly touchy when the subject was brought up.

Their visit to Oslo, Norway in 1967, was not the first or last, but it was one where my uncle unintentionally kicked me spinning head first into the emotional ocean of puberty.

On the evening of their arrival, my uncle came into my room just as I proudly played Sgt. Pepper’s for my cousin on the gramophone. Earlier in the year, during summer, I had taken the tram downtown to buy the vinyl record. Oslo still had those old trams running at that time. I remember standing in the open clearing at the far end of the tram, holding on the record like a precious jewel.

“Well, The Beatles are good, but I have brought something else for you,” my uncle said in a secretive voice, and handed me a record with a very different, and much more modest, sleeve than Sgt. Pepper’s. “The record just came out,” he explained. “It is by a Canadian singer, Leonard Cohen, and this is what is really hot right now.”

I had never heard about the guy. The sleeve looked kind of gloomy. The title of the album, Songs of Leonard Cohen, also told me nothing. The sleeve made a kind of gloomy impression. For sure no match compared with the artwork on the sleeve of Sgt. Pepper’s. This was not a record I would have picked up in a store. But whatever doubts I had, I also knew my uncle was something of an expert on music. Much to the relief of my cousin, I placed Sgt. Pepper’s back into its sleeve and put on Leonard Cohen. And within seconds a dam burst and my life was transformed. I was another.

“Take me back,” Van Morrison pleads in one of his songs.1 “Way, way, back,” he continues. While Van The Man had Belfast of his youth in mind, these early recollections of my uncle take me way back to Norway in the late 60-ties and early 1970-ties.

Although one could more profoundly feel the silence during the 50-ties and 60-ties, a kind of innocent and soft tranquillity was still the order of the Norwegian day. On those long, wintery days the evenings were endless. One had the feeling that time was something happening elsewhere, because in Norway nothing seemed to changed. Year in and year out King Winter silently shrouded the landscape with his royal mantle.

In spite of the German occupation during the 2nd WW, Norway had to a large extent remained an idyllic place, unperturbed of the early calamities of modernity. The world was far away, at least mentally. Snow was abundant and the frosty beard of King Winter left its stain on every window. As a young boy I brought my hockey skates with me to school. Day after day we played ice hockey on the frozen lakes until it got too dark to see the puck. It was easy to get the impression, as my uncle not failed to remark, that the quiet Norwegian capital, Oslo, in wintertime resembled a desolated town in Siberia. Reindeers and polar bears danced merrily in the streets at night, and people used skis to get to work. The few restaurants in town closed before a true bohemian had managed to brush his teeth (or put them back in again), and the menu was sparse; meatballs, cooked fish and potatoes. Shops closed at five in the afternoon at the very latest, and no, absolutely no alcohol was served on either Sundays or any other holiday, even in some cases on the day before a special holiday. No loud sound of electric guitars disturbed one’s sleep. The wide screen cinema showed The Sound of Music. It was a huge success. People saw it over and over again. At least one elderly lady saw it 125 times. There was one radio station and one TV station. Transmissions ended at 10 PM. After that you could hear your neighbour lose a hairpin on the floor.

To some this may sound like a lost paradise. But according to my uncle, things were not as picturesque as they appeared. In his eyes the meaning of life was not only about falling snow, deserted streets and closed shops. Not to mention the lonely woods where trolls still lurked, or that farmers fed the animals before they sat down to eat. If they did not, the goblins and other subterranean beings, of which there was a rich category in Norwegian folklore, would become angry and take revenge.

“It is like Siberia,” was my uncle’s blunt description as he shivered from the cold, hat and coat covered with snow, with an expression reminiscent of a lost dog. Then again, Oslo in the early 1970-ties was a colourful fiesta compared to Oslo a decade earlier.

“One could walk down the main street without meeting anybody!” he proclaimed years later, still astonished by the strange phenomena. It starts getting dark already at three in the afternoon, there’s snow in the air, falling, falling, and nobody’s out, and here comes Olaf, my uncle from Barcelona, Spain, walking stick at hand, his soul full of jazz, ready to party.

Oslo evenings in the early 1970-ties had no intension to make you feel up beat. The heat was definitely not on. King Winter held a harsh court in his realm. Besides, the world was far off and, as we all knew, a quite dangerous place. Sinful too. From early childhood on one heard dreadful rumours about sin. It could strike any moment and worm its vicious way into a man’s heart. Once inside it would twist his mind and bend his knees, and you’d loose your skies and freeze to death in the snow. While the North Sea protected Norway from connecting directly with the surely sinful European mainland, there was a steady inflow of worrisome reports in the Norwegian press about how sin flourished across the border.

Through the decades there has been various interpretations of what is considered a sin. One of the major achievements of the 68-generation was their remarkable and successful effort, with a little help of one of their friends, Chairman Mao, to transform the concept of sin from its rather timid protestant reference to purgatory in the afterlife, to a more immediate and practical application to life here and now on earth in the form of the unwritten norms of political correctness. And should you believe the Cultural Revolution was a mere Chinese event, think again. Europe is still suffering from it.

Back in the good, old days before rock and roll, a solitary walk through the streets of Oslo could make you feel like the last man alive. And if you happened to love flamenco, as my uncle did, it was as if civilization had hit a impenetrable fog somewhere out there in the North Sea.

“The only person I met was an old lady,” Olaf explained after a stroll through his mother’s maiden city. “I lifted my hat and said good afternoon. She didn’t utter one word, but clutched her bag firmly in both hands and stared at me with wide-open eyes as if I was a ghost!”

What further confirmation that Oslo was a part of Siberia did one need? God knows what kind of strange bird that old lady thought he might be. An agent for the Pope in Rome, no less?

My uncle smiled. My father tried to. It was easy for Olaf to laugh about it. In a couple of days he would be returning back to sunny Spain. My father, though, was to stay in Oslo for the rest of his life. For him there would be more winters and more snow, stuck as he was in his mother’s country. In all fairness it should perhaps be mentioned that the old lady’s staring glance might have had something to do with my uncle’s strong German accent. His Norwegian vocabulary was not that good either. He knew a few words, barely enough to buy a ticket on the tram or make a short remark. A couple of calvados would have been needed to make a speech, but overall it fell off the road when it came to small talk. My father and uncle were both half German, half Norwegians. Their father was a merchant from Hamburg, their mother the daughter of a Norwegian priest. While my father continued the family business, my uncle persuaded a wholly different career. Not that it mattered to the descendants of the brave Vikings; people on the streets of Oslo were not used to Germans when my father and uncle first strolled around town in the 1930-ties. That would soon change as they got to know a lot more Germans a few years later, in April 1940, when Hitler crushed down on the dreamy Norwegian innocence like a ferocious vulture.

“The doctors gave him hell!” my father told me. “I do not know how it happened, or what really is wrong with his leg, but I believe being told that when he was a baby a nurse accidentally dropped him on the stone tiles on the floor, and Olaf’s leg was mutilated for ever.”

I was about 13 to 14 years old when he for the first time talked about my uncle’s troublesome leg. It made a huge impression on me. For my inner eye, I saw what happened. Some clumsy nurse, clad in white frock, is only thinking about getting laid. The empty promises by made by a lousy Günther last night in a worn-down Bierstube ringing like wedding bells in her head. Or maybe the nurse was a whimsical wreck? On the verge of nervous breakdown due to the harsh working conditions under the patriarch in Elbschausee, Hamburg? Now, there’s a chance my father and I are both wrong, and nobody will know whatever caused the problem. Perhaps Olaf was born with that damned leg. However, as my father spoke, I had this vision of a big nurse dropping a baby onto the hard, cold stones. The left leg getting deformed and Olaf crippled for life. The vision was to haunt me for years.

I did not share the vision with my father. I’d like to believe it was out of modesty, but although I’ve had my moments where I too had reason to strongly doubt I had it, I admit it, for once, was due to common sense.

As it was, I had at that time already shared a few other visions with my parents; on the walls of my room were a couple of giant posters. Che Guevara and Jimi Hendrix. Marx was up there for a short time too, but when I read in a biography how he fathered a child outside of marriage, the Lutheran protestant in me got the upper hand and he went down in a hurry. Jimi replaced him. Gurus live as they speech or refrain from speaking. And Che? That was more like a romantic manifesto than a real person. Kind of a Jim Morrison figure before The Doors made their first record. Eventually he had to climb down from the wall too. I’m not sure what replaced Che, but I know what should have: Jane Fonda in Barbarella. During my years in school, I had the foolish notion that sharing visions with my teachers and classmates was an utterly brilliant idea. Somehow carried off by a persistent eagerness to not only explain, but rather live out, at least some parts of my visions, I, in my great naivety, completely forgot to take into consideration that the head teacher was no Jane Fonda, but an ardent member of the Norwegian pro-Soviet Communist Party.

This apparatchik Barbarella wore a fluorescent, greenish coloured warehouse coat in the classroom and had red iron spikes instead of hair. When she was in a good mood, which occasionally happened to coincide with the last day before school closed for summer, she used to tell us about her past wonderful summer vacations in DDR (German Democratic Republic). She could have gone to the moon for all I cared, as long as I didn’t have to see her in a bikini.

Thus by the time I listened to my father’s account of my uncle’s troubled leg, I had learnt to control my former eagerness and when to keep my mouth shut. Well, sort of.

“They tried a lot of therapies on Olaf and his leg,” my father continued unhappily. “Specialists were called in. One of these therapies were particular painful. They stretched out the leg and put it in some kind of wooden box to keep it straight for a longer period of time. It must have been terrible. I can still hear him moaning. Olaf himself did not complain. He moaned silently, but never complained. That therapeutic cure did not help a thing. None of the therapies helped. To the contrary, they only caused him pain. And as we other young boys were climbing trees and running around in the garden, Olaf had to sit there and watch us play.”

At this point I have another vision. Perhaps it is a kind of mental valve to hide the full impact of the sad yearning in my father’s voice. I didn’t dwell on the subject, but instead let myself be engulfed by it. It is not of Jimi Hendrix playing guitar with his teeth or Che Guevara’s romantic posture. It’s a vision about a certain kind of heroism not seen on posters.

What I see is a garden. It’s a sunny and warm day in the height of summer. I see boys with neatly combed hair running happily around in their shorts. Laughter and shrills. Catch me if you can. The cry carries all the way up to the big house, through the open windows and into the room where Olaf is sitting with his leg in that therapeutic wooden box, listening to the laughter and happy shrills of his two brothers playing outside. The room is hot and the air stiff. But one thing is the body, frail as it is, another thing is the soul. It’s born free. In his heart Olaf is right out there with the other boys. In his mind he is climbing the old trees and running across the lawn. The movements are rash and joyful, the garden bigger than the ocean and full of secrets.

And there my vision ends.

In real life my uncle used a stick and walked with a slight lump. Oddly enough it became his hallmark. I do not know what impact the walking stick, and the sight of the thin, frail looking youth with those big, kind eyes had on women, especially the young and careless, but I have a feeling it was a not made for romance. Heroes don’t come limping out on the dance floor with a walking stick. There’s a saying that everything is in the eyes of the beholder. Many years later, when he and I walked through the narrow, cobblestone streets of the small, Spanish fishing village of Cadaqués at night, I secretly admired the modest and graceful way he carried himself.

My uncle, Jürgen Olaf Hudtwalcker, using only his middle name, Olaf, was born in Hamburg on 12 September 1915, as the youngest of three brothers, and died in Barcelona on 23 April 1984.

The three boys, Dierk, Charly and Olaf grew up together in a big house. There was a garden where the boys used to play, and the big house was full of strange paintings made by equally strange artists. Their father left early in the morning and returned late in the afternoon. Unknown to the family of five, dark clouds were gathering over the river Elbe. In 1928, the year Olaf turned 13, their mother, Sigrid, died. She came from a country far away up north, a country the young boys had never visited, but only heard about. For some time, she’d been slowly withering away. Again the doctors called in, again the stale air in waiting rooms of the specialists, again the long days of uncertainty. However, this time the doctors suggested no cures and mentioned no therapies. The brain cancer was incurable.

They buried her early in the spring at the family grave at Ohlsdorf cemetery. The three boys respectfully a few feet behind their tight-lipped father. Afterwards the big house felt empty. Sounds were swallowed up by the wallpaper. The garden still there, of course, the old trees too, but the shadows in the corners had grown and their father’s face was pale with worry and sorrow.

Sigrid had been a breath of fresh air into the dull stiffness of the Hamburg bourgeoisie. By birth he was a part of it. By profession he represented it. Yet these strange and rebellious contemporary painters had caught his attention. Although their world was light years away from the stiff formality surrounding him, their works talked to him in a language he recognised. But that was as far as he would go. He had always reined in his restless mind. Emotions were not to be spoken about. And now, a widower at 48, still relatively young and with the sole responsibility for the three young boys and the family business to run, he was vulnerable. The feeling of gloom in the house only increased when news came that the oldest son, Heinrich Dierk, who was working in a bank in Buenos Aires, was ill with tuberculosis.

The two younger brothers had always admired Dierk. He was great fun to be around. Sporty, witty and energetic, Dierk had been the undisputed choice to lead the family business into the next generation. But the reports from Argentina were grave. Soon thereafter Dierk barely managed the journey to a sanatorium in Arosa, Switzerland, where he died in 1931.

In the garden surrounding the big house in Hamburg, the shadows grew longer and thicker. The overall feeling of purpose lost among the falling leaves. Then, from somewhere in the shadows, a woman emerges. Black hair, a broad and stocky stature, a heavy south-German accent. She looked like the opposite of their deceased mother. For once looks did not deceive. I believe I’ve read somewhere that the human heart is a lonely and mysterious place. There are questions without answers and riddles best left unsolved. A few years after the death of his first wife, Heinrich Carl re-married. If some marriages are made in heaven, it soon became apparent to the adolescent sons that the whereabouts of heaven depended on the mood of their stepmother. Better keep those two spoilt boys on their toes.

People show their discontent in different ways. In 1935, Olaf, who had showed such a stoic attitude at the hands of the doctors, and endured the useless and painful therapies, turned 20. His older brother, Carl Heinrich had, as soon as he had completed his studies at The University of Münich, been sent to Christiania (Oslo) to start as a trainee in the family business in Norway. Of the original three sons in the big house on the banks of the river Elbe, Olaf found himself alone with his walking stick under the roof of his father and step-mother.

One didn’t have to look twice to see he could not take it.

At the same time, outside the garden walls, strange events were unfolding. It was as if somebody had put a drug into the drinking water of the German population, making the whole nation suffering from hallucinations. As Hans Magnus Enzenberger writes about the Weimar Republic in his essayistic novel Hammerstein:2 “We shall be grateful we were not there.”

Civil war was in the air. Violent fractions and militias, from the far left to the far right, were out in force. None of them gave a Reichsmark for democracy. Enzenberger list them up: the SA, Roter Frontkämpferferbund, Stahlhelm, Hammerschaften, Reichsbanner, Schutzbund and Heimwehr. During the dying days of the Weimar Republic, in 1932 and 1933, ten years after the hyperinflation in 1923 had sent the German economy spinning out of control, these groups openly fought each other on the streets. Furthermore, the stock market crash of 1929 with the ensuing financial crisis did not ease the economic burden of the Versailles Treaty.

Enzenberger writes that certain conditions in the treaty, and the allied occupation of the Ruhr area, created “furious thoughts of revenge in the German society”. (The final payments ended up being made on 4th October 2010). A feeling of powerlessness made people seek shelter within extreme positions. And everybody underestimated the short guy with a small, black moustache, the creature of darkness, born and nourished by the chaotic circumstances. With his right arm raised, he was to spin Germany head first into a euphoric and collective hysteria not seen before in Europe.

Around that time, while people marched through the streets in brown uniforms to Teutonic horn music, my uncle left his childhood home. For a while he lived in a basement in the St. Pauli district of Hamburg together with a coloured woman, playing American jazz music on the gramophone and participating in meetings of the White Rose movement. But foremost there was music, the language of the soul. And a very different one than played by the marching bands outside in the streets. Coming out of the gramophone in the basement in St. Pauli was a new kind of music coming from the other side of the Atlantic ocean. You could feel the beat with every nerve in your body. Even in a crippled leg. The sound of the soul. After the 2nd WW, in the 1950-ties, when Olaf toured Germany as an impresario for black, American jazz musicians, Miles Davis told him: “You are one of the few.”

But that was way into the unknown future. Right there and then, in the second half of the 1930-ties, nobody in Germany could in their wildest fantasy imagine that less than twenty years later, the young boys and girls would not happily milk cows in their Bavarian Läderhosen, but instead line up to listen to music plaid by descendants of African slaves. However, to the young Olaf in the early 1930-ties, living in Hamburg also meant living in the shadow of his stepmother. That was no place to be. Instead he yearned to be around people he could really connect to and shared his love for jazz, and in 1935 he moved to Berlin. Not long after his arrival there he became a member of the illegal Hot Clubs. A couple of years later, in 1937, that activity was expanded to include also a membership of the Hot Club de France. Olaf stayed in Berlin until 1941, when conditions forced him back to Hamburg in order to assist his father. The war had started to take it toll. Hamburg was bombed by Allied warplanes and his father’s factory went up into flames. When the nightmare finally ended, Olaf wasted no time and immediately returned to his beloved jazz. But now there was a major difference: he did not risk being arrested. And Olaf jumped right at it. From 1945 on he wrote articles and held several lectures about jazz. In 1947 he became chairman of the Hot Club in Frankfurt. From 1948 he had his own radio programme, and was President of the German Jazz Federation between 1955 and 1966.

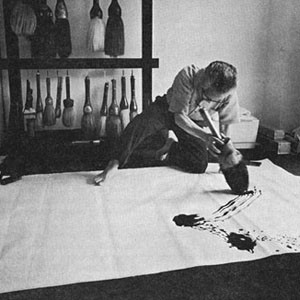

He engaged in other activities too, had his own art gallery, Galerie Olaf Hudtwalcker, of course located in the House of Jazz in Frankfurt. It was not an art gallery to look for the über-romantic landscapes we are so fond of in Norway. Whereas his body might move slowly, the soul was not about to be dragged down by gravity. The times they were a-changing. His gallery was a show-room for modern art. Among the exhibitions were works by the Japanese Sho-Master Shiryu Morita.

When I asked him why he did not visit Japan, especially given his interest in Japanese painters, Olaf said the leg made such long air flights impossible. Fortunately for me, however, the leg did not stop him from travelling to Paris.

One morning in early autumn I started reading Henry David Thoreau’s Walden on a slow train from Oslo to Paris. Instantly spellbound by the simplicity of his worldview and the style of writing, I stepped out of Gare du Nord as a dedicated follower of Thoreau, longing for a true closeness to nature.

In after sight it’s easy to see the timing was not perfect. Paris, for all its splendours, was no woodland where a simplistic minded devotee of Thoreau could live in quiet harmony with nature. The Latin Quarter was probably as far from Walden as one could get. I sought refuge in the Parisian parks while I fought a desperate, yet steadily losing battle between my new ideals and the urging realities of the city. After a couple of weeks Thoreau was defeated, and while Walden burned, I yearned for something more up to date to get in tune with whatever I felt was going around outside and inside me. I tried my luck with Jack Kerouac. No deal. I tried reading Allen Ginsberg. Didn’t work. At a party up at a loft in Montparnasse a guy looking like William Faulkner handed me a book by Henry Miller. That triggered things. Soon I was hanging out around Place Clichy. Days became nights and nights turned slowly into a blur until it dawned on me that once again I was flaying a dead horse. Dreaming dreams others had already dreamt made no sense. No point in thinking thoughts that had already been taught. The past could be recalled in books or on a screen, but was no place to live one’s life. Furthermore, the Paris I saw did not bear the faintest resemblance to either Hemingway or Henry Miller. The moveable feast had long ago moved down memory lane. Or so I thought. It all changed for 36 hours when my uncle came to visit me, and we late on night ended up at the restaurant La Coupole, famous for its art deco interior and oysters.

Inside was glitz and glamour all around. Posh and busy waiters, fashionable and high profiled men talking to fashionable and high profiled women. The place bore no resemblance at all to evenings in a Norwegian ski lodge. Whereas I felt slightly like a fish out of water, my uncle’s eyes immediately got a new sparkle in them and his cheeks got a full, rich colour. Sniffing the air, and taking it all in in deep breaths, like someone released from a Siberian concentration camp, he finally said quietly:

“Oh, Europe!”

We found a table and sat down. Eventually one of the waiters mercifully discovered our lost souls, and we had just raised the glasses and tasted the wine, when two strikingly beautiful ladies came in the door. Some people know how to make an entrance and some haven’t got a clue. One can generally tell which is what by how a crowded restaurant like La Coupole suddenly gets quiet. With every male eye in the room glued to their bodies, the ladies were oblivious to causing such distraction, of course. As they gently moved in our direction, a shiver ran up my spine. It was not like the feeling you get when snow got underneath your sweater. Before I was able to analyse this phenomena further, the two ladies sat down at the table next to us. My heart skipped a beat. And, as if waking up from a long winter’s sleep, the restaurant slowly became alive again. While my face resembled a ripe tomato, and my breathing was as slow and heavy as if I had been skiing up hill for hours, my uncle, however, by that time well in his early 60-ties, wasted no time. Before I knew it, the two tables were turned into one and there was a party going on.

The ladies courtly introduced themselves as Madame Bovary and Pauline Hemingway. Madame Bovary was coloured. Her skin, of which the tight leopard patterned dress revealed a great deal, was black as the night outside. I found their names strangely odd. Especially hearing the last name Hemingway stirred emotions within me. It could not be, I thought, yet she was so close I could stretch out and stroke her hair. Just as I was to about to ask, somebody kicked my leg and a familiar voice said: “Let’s drink to the ladies, nephew!” We drank and then drank some more. The place became better and better. Soon the waiters were swarming around our table like bees attracted to a pot of honey.

I became aware of my uncle intently studying Madame Bovary’s face. It was as if he was searching for something. I found it mildly annoying, but Madame Bovary did not seem to mind.

“You like what you see, dear?” she poured softly in a deep, rich voice. “You want to see some more, don’t you, baby?” she continued and the tip of her tongue touched her red upper lip.

Something seemed to be stuck in my throat. It itched as hell. The sight of the tip of Madame Bovary’s tongue joyfully caressing her red lips made my heart beat like a puppy having lost its mother. “I should have stayed in Walden,” I thought frantically and grasped for air. My uncle, however, paid no attention to the torments of his nephew.

“Yes, absolutely, dear!” my uncle replied, “But, you see, you remind me of someone … and I …,” he added in a low and rather intimate voice, like he was talking to himself.

“Oh, c’mon, daddy! You’d bet I’ve heard that before. There’s no need to be shy about it, you know, sugar, ‘cause that’s what they all say,” Madame Bovary softly purred and blinked with her left eye to Pauline Hemingway.

My uncle, lost in thoughts, did not reply, but unperturbed continued his careful studies of Madame Bovary’s face. The whole thing was starting to feel a bit strange, like being on board The Titanic after it had hit the iceberg. I felt an urge to say or do something. Say what, to whom? Even under usual circumstances I was no big talker, but right now my tongue was glued to my mouth. Maybe a sip of water will help, I thought frantically.

“Honey, you got a match?”

Something soft and warm touched my knee. 10,000 volt shot through me. My head jerked upwards and I looked straight into Pauline Hemingway’s mysterious, deep blue eyes.

“I didn’t scare you did I?” she said with a smile. “Now, that would be too bad. You’re such a sweet looking, boy. I bet the girls like you a lot. Don’t they?”

My head felt like it had been stuck inside a Finnish sauna for a week. I fumbled for the matches, but my hands were all sweaty and shaking, and just as the matchbox landed on the floor beside Pauline Hemingway’s high-heeled shoes, my uncle leaned closer to Madame Bovary.

“Eartha Kitt!” he suddenly burst out with a happy grin. “That’s who you resemble. Sorry, it took me so long to remember, but in company with such two beautiful ladies one’ mind easily gets a bit … distracted,” he smilingly offered as explanation.

For a second Madame Bovary’s beautiful face got a puzzled look. She looked at the floor, looked at Pauline Hemingway, before slowly lifting her head towards my uncle. I could have sworn I saw a teardrop in her eye, but not only had I lost count of how many bottles we had emptied, but by now I could have seen Santa on a reindeer-sledge riding down Boulevard Montparnasse.

“You know, daddy, that’s the most wonderful compliment any man ever gave me!” Madame Bovary said slowly. The next minute I was sure Santa had arrived. Without uttering one more word she threw her arms around my uncle and kissed him tenderly on the cheek.

“Now ain’t that something, nephew!”

My uncle’s happy face was beaming proudly.

“I got a hunch this is going to be a great evening. Don’t you think so, ladies?”

“It already is, honey!” Madame Bovary replied with a delightful laugh.

“All right, then, let’s drink to this wonderful occasion!” my uncle exclaimed. With a secretive smile, he turned to Pauline Hemingway and said in an almost youthful voice:

“Pauline, dear, be an angel and get that waiter over here, please!”

Later that evening on my uncle insisted the oysters were magnificent. I had no idea we had even ordered them. Most of the time my eyes were glued to the fishnet stockings on Pauline Hemingway’s gorgeous legs. I could tell my uncle was a bit annoyed by the sheepish look on his nephew’s face, especially when I my heart melted into Pauline Hemingway’s eyes. But I could not help it.

They were mysterious and deep.

Just like Walden Pond.

As Olaf grew older, his leg got worse. Although he kept his old apartment in the House of Jazz in Frankfurt, and continued his regular broadcasts in Radio Hessen, he spent most of his days in Barcelona.

It was already years since we had walked together on the narrow and dimly lit cobble-stoned streets of Cadaques, the sound of his walking stick softly thumping against the house walls. The old fishing village of Cadaques, surrounded by steep mountains, had been built around a natural bay, still serving as harbour. As we came closer to the bay, we could hear the sound of the waves rolling against the rocks in the soft and warm Mediterranean night. After a day underneath the hot sun, we headed towards our usual waterhole in the city square. We discussed all kinds of topics, from music to politics, but no matter how far off our talks wandered, he would at some point always came back to Goethe. As a young man, his Italian journey, the older statesman as portrayed Thomas Mann’s Lotte In Weimar, a book everything in me strongly opposed. I revolted against his philistine portrayal of Goethe as a mix between a fat private banker and a provincial, German pig farmer. Thomas Mann did not see the individual, but the other.

I also remember the smells and the sounds from the streets of Barcelona, and the sight of my uncle’s enormous record collection. Occupying wall after wall in the apartment, it was a treasure cave for a curious youngster, offering gem after gem of LP’s never to be seen in a Norwegian record store.

Throughout his life, Olaf had always been up front when it came to finding new trends. He discovered jazz when most people had never heard about it. He promoted modern art at a time when Europe was still trying to get back to its feet after the war. And when people got busy wearing flowers in their hair, dropping acid and turning up the volume of their electric guitars, Olaf went for something entirely different; Spanish flamenco, played on acoustic instruments, and performed not by prophesied rock stars, but by gitanos and gypsies from the outskirts of Barcelona and Andalusia.

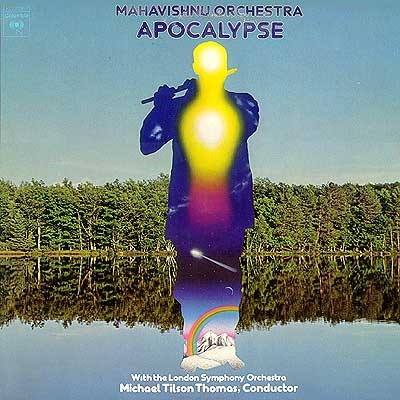

In the early hours of an afternoon in 1974, Olaf and I had been listening to Apocalypse, the new album by the equally new edition of The Mahavishnu Orchestra. I could as well have been listening to Gurdjieff singing in the shower. However, that certainly was not a topic I wanted to discuss with my uncle, the former President of the German Jazz Federation.

The living room was bathed in sunlight, a bottle of wine on the table, the sound of the busy Barcelona traffic from the streets down below. The Mahavishnu Orchestra had had their say. They’d played their tune. The music of the yogi having died out, it was time to move from the

east to the west, and into the sphere of the commissar. We talked about the latest developments regarding the Russian author Alexander Solzhenitsyn.3 At that time Solzhenitsyn was a kind of fugitive from the Soviet Union. The Kremlin party commissars had either expelled him or let him go. Apart from the fact they took away his Soviet citizenship, the issue was open to interpretations. What was beyond interpretation, however, was that Solzhenitsyn had arrived in Western Europe like a honourable guest everybody praised, but nobody dared invite home to dinner. The academic elite did what they usually do when they cannot blame America; looked another way.

Olaf was not at all happy about how Solzhenitsyn was received by intellectual circles in the West, especially in Germany, and became more and more agitated, until he at one point could not resist himself anymore, but blurted out:

“The European intellectuals are traitors!”

Anger flashed in his eyes, the voice sincere.

What?

I could not believe my ears.

Was this my gentle uncle talking?

I emptied the glass in a hurry and quickly refilled it. My mind felt like being invaded by wasp. I had another go at the glass. Didn’t Olaf know that I went to the most experimental high school in Norwegian history? A school where the pupils drifted in and out of the class room at their own leisure, teacher present or not, or sat for days on end playing cards in a room full of cigarette smoke and the nauseating smell of Lapsang souchong tea. And if that did make one lose every sense of direction, then the sound of someone humming a guitar, trying to sound like Roy Harper singing his silly anthem “I Hate The White Man”, was enough to make you run for the woods.

There were three kinds of pupils in the happy-land of the experimental high school: The realists for whom life was a logarithm, the Marxist-Leninist for whom life was joyless injustice and then a strange mishmash for whom life was a chaotic mess. It was in this crowd one found the pale poets and guys in black leather boots playing Chicago blues on their mouth-harmonicas. Some of them carried volumes of Dostoevsky around, sat up all night, chain-smoking and drinking bottle after bottle of cheap red wine, discussing the writings of André Breton and art of Max Ernst. The Marxist-Leninists couldn’t make head or tail of them. Even the most paranoid hard-core follower of Stalin had to agree these guys could not be CIA undercover agents.

I thought I had heard some quite outrageous statements, but nobody had ever looked me straight in the eye and said the European intellectuals were traitors. With one sentence my uncle had shattered the pillars of conventional wisdom. Up to that moment, it had been relatively easy. Uncle Scrooge and his cronies of cruel capitalistic lackeys on one side, the horny Karl Marx and his ashen faced sufferers of injustice on the other.

Feeling as happy as a viper out on a bleak winter’s day, I crossed the left leg over the right. Then I crossed the right over the left. Left was right and right was left, and what the heck was I supposed to say?

Well, there was no need to be a doctor in political science to grasp that my uncle’s remark would not earn him a degree in diplomacy. Neither would it endorse the beginning of a lasting friendship with anyone I knew. Even to the liberal minded this was way out of line. You’d be ostracized for life.

The more I thought about what he had said, the less I liked it what I thought. The implications horrified me. One of them would necessarily be that the army of joyless revolutionaries would end up as pedantic government bureaucrats. And thereby free to continue their labor of contempt for Europe and the West from within? The political 1970-ties was nothing but a sideshow camouflaging what was really happening to the European mind? The army of intellectuals, students and artists were in their own eyes impeccable, on a moral high ground, united in the dream of a world were justice, whatever that was, ruled. That the Lady of Justice often was portrayed blindfolded did not create a shadow of doubt. Fuelled by a loathing of everything they despised, which happened to be their own cultural identity, they marched through the streets, utterly oblivious to the fact that, however repulsive it might be to the bourgeois mind, European culture had been not created by capitalistic lackeys, profit mongers, political commissars or any academic elite, but by heretics, alcoholics, thieves, syphilitic loners and an unholy bunch of individuals who only had one thing in common: the courage to stand up against the believes and dogmas of their time.

The multimillionaire artist of the new millennia building castles in the sand was a new phenomenon driven by the surge of black gold, oil, which during the last decades had inflated the values of art (and deflated most other immaterial values). It’s worth remembering that Van Gogh never sold a painting.

The minute or two which had lapsed since my uncle with had shattered the world I up to then thought I knew, felt like an ocean of time.

I looked across the table.

My uncle held his hands in his lap, seemed lost in thoughts.

Now, my family has never been actively engaged in what the Germans calls Zivilisationskritik. Through generations most of our lot had been merchants, peddling everything from cheese to Cod Liver Oil. And, as with every merchant, it is the matters of the day that gets the attention. If others get a kick out of solving the problems of the world, well, go right at it. Live and let live. We have other things on our mind. Not necessarily as important, just different. Like counting drums of Cod Liver Oil. Stretching it far, the kind looking, and usually very gentle, Olaf, could perhaps have passed as our version of Rousseau, but I had huge difficulties regarding him as a vengeful impersonation of Oswald Spengler.

On 19 March 1945, deep down underground, inside the Berlin bunker, with the Red Army rapidly advancing and the Allies having reached the river Elbe, Hitler ordered the destruction of what remained of German industry, communications and transport systems. In Hitler’s own words, the German people had “cowardly failed”. If he did not survive, neither should Germany. It deserved to be destroyed. Fortunately the order was not carried out. However, he had successfully managed another kind of destruction. Towns could be rebuilt, bridges too as could railway tracks and roads. But healing the soul of a nation was another matter. There’s many ways to look at it. Plenty of books, movies and studies have been made. One could cut through it all and simply say that Hitler had made tabula rasa of German culture. In the wake of the Nazi Götterdämmerung, Goethe and Schiller had been thrown away as useless wreckage, and their Doppeltgänger installed as spiritual leitmotif. Although Germany had been spared the physical destruction ordered by Hitler, he had inflicted a wound so deep it was like injecting a poisonous thorn into the German Geist.

In the shadow of Goethe’s house am Frauenplan in Weimar, Auschwitz had risen as Klingsor’s new castle. An everlasting memorial of what Germany not only could do, but to the atrocities it had committed. After the fall of the 3rd Reich, the accepted reasoning was that only a thin layer of culture prevented man from turning into a beast. Even the most civilized nation could at any given moment mutate into a barbarian nightmare. Therefore man had to be protected against himself. In the post-Hitler world, the individual was, in the eyes of the ruling elites, a lose canon on deck.

Olaf, though, saw things differently. To him, the failure of the European intellectual elites, in this case highlighted by their treatment of Solzhenitsyn, meant that they, about 30 years after Hitler, were willing to compromise on freedom and democracy. But these were values hundreds of thousands had died for to protect. The beast had risen, and only sacrifices almost beyond comprehension had managed to defeat it. And whereas Luther, poor chap, had to nail his thesis on a church door in Wittenberg, the elites of the modern media-age had a lot more sophistaced methods to drive their message deep into the European soul: The individual can not be trusted.

But the untimely arrival of Solzhenitsyn served as a stark reminder of the enormous positive potential of the individual. Unlike his peers in the West, Solzhenitsyn did not suffer from self-loathing and hatred against his cultural identity, but came in through the iron curtain after years in various Soviet Union GULags,4 just as the European intellectual in the 1970-ties flirted with the very same political ideas which had locked him up in the forced labor camps.

Outside the sun was sinking. The noises from the streets below had quieted down, the bottle of wine now empty. My uncle had been sitting down for too long. The leg was painful and stiff. He massaged it with his hand before he got up with an effort, and slowly limped over to the window. Looking at the approaching night, he said in such a low and tired voice I barely heard the words:

“And in spite of everything my poor Germany remains the heart of Europe.”

Many a full moon has crossed the river of time since Olaf and I last met. Yet my mind often

wanders back to that afternoon in Barcelona. I see Olaf’s silhouette against the burning evening sky, and hear his voice.

Regardless of the fancy things money can buy, the spellbinding wonders of the never sleeping cyber space, and electronic gadgets soon able to fulfill every secret desire, it’s still all about soul. Or the lack of thereof. That’s the core and that’s the root. Abstract theories do not propel history, what lives inside people and inspire their actions does. Becoming aware of the existence of the idea in reality is the true communion of the soul.

John Michael Hudtwalcker, 2015

The author would like to mention that as English is not his native language, he asks to be excused for possible grammatical errors and the text not being as literary fluent as it should have been.

Links

Biographies – Jürgen Olaf Hudtwalcker – So Fing’s An

Biographies – Jürgen Olaf Hudtwalcker – Die Frankfurter Jazzszene in der Nachkriegszeit

Susanne Schapowalow german Wikipedia article

Notes

- Hymns To The Silence Van Morrison, 1991

- Hammerstein oder Der Eigensinn. Eine deutsche Geschichte. Hans-Marius Enzenberger Suhrkamp Verlag Frankfurt am Main 2008

- Alexandr Solzhenitsyn (1918 – 2008), awarded Nobel Prize in literature in 1970. Among of his most known books is the trilogy: The Gulag Archipelago (published 1973 – 1978).

- GULag; Government agency (“Main Camp Administration”) administering the main Soviet forced labor camps. The term GULag is also sometimes used to describe the camps themselves.

www.hudtwalcker.com 2015